Incidental findings in radiology can be a cause for concern for patients, their doctors, and their families. It is important to understand what these findings are and what they may mean for your health (for patients) or the health of your patients (for providers). In this blog post, I will discuss the definition of incidental findings, common types of incidental findings, and what you need to know about them. I will also provide tips on how to best manage some of the most common incidental findings.

What is an Incidental Finding?

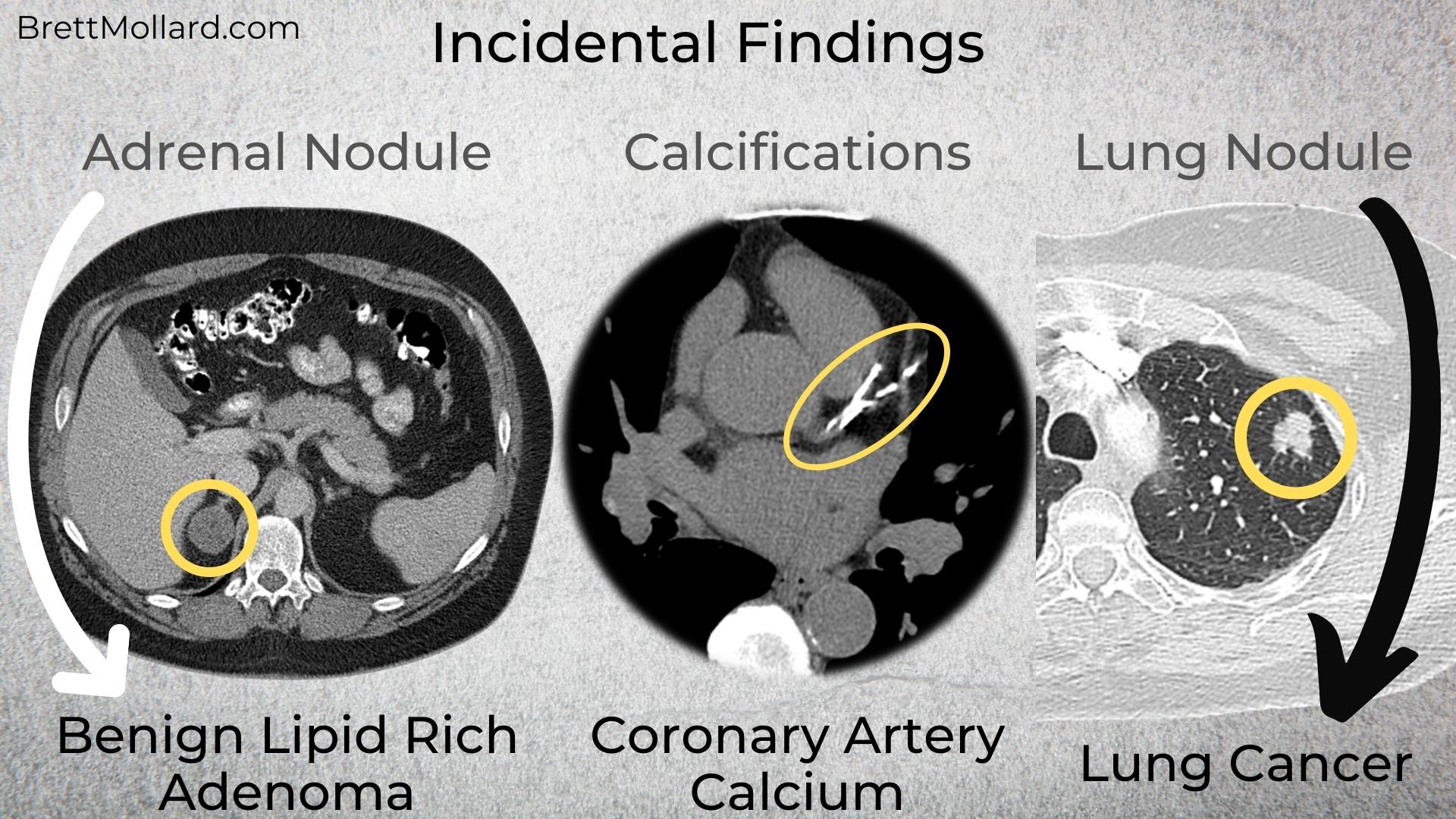

An incidental finding is as its name describes: a finding that was not the main focus of a radiology exam and was found by chance. Incidental findings can be further broken down into two types: determinate findings (the findings are diagnostic of an entity – we know what it is) and indeterminate (a finding is made, but the imaging features are not diagnostic, frequently requiring additional testing to obtain a diagnosis – we don’t know what it is). These unrelated findings may be of clinical importance, such as incidental cancer requiring treatment, or of no clinical importance, such as a benign renal cyst (a sac of fluid that can safely be ignored).

Incidental tumors are typically the most concerning and anxiety-provoking unrelated findings we make and can be either benign (non-cancerous) or malignant (cancerous). Benign tumors can be safely ignored while malignant tumors require treatment or surveillance.

Anytime a person is imaged, there’s a chance of making an incidental finding. And whenever a radiologist looks at an examination, we not only try to address the clinical problem at hand (such as pain) but also try to identify anything else that could prove problematic in the future. We want to identify malignant cancers while they’re curable and identify pathological processes to help guide management and prevent bad outcomes in the future. For example, identifying coronary calcium indicative of coronary artery disease in a young individual allows for a change in lifestyle and starting heart-protective medications to prevent or delay a future heart attack. This can be a defining moment in a patient’s life.

The scope of a radiologist is not only to address the problem at hand but also to identify anything of potential future significance while being mindful of the costs of associated follow-up testing. This is one important area where we add value in medicine.

Prevalence of Incidental Findings

Prevalence of incidental findings varies by imaging modality (ultrasound, CT, MRI, etc.) and the body part being imaged. Several meta-analyses exist (in a meta-analysis numerous research articles are reviewed and data is pooled to give greater confidence in the results) evaluating the prevalence with a recent study in the BMJ from 2018 reporting the following incidental finding rates:

- Brain MRI – 22%

- Spine MRI – 22%

- Chest CT – 45%

- Cardiac MRI – 34%

- CT Colonography (Virtual Colonoscopy) – 38%

In this list, you can see that we frequently discover incidental findings on all kinds of exams.

The prevalence of malignant incidental findings was 11% across all studies (11% of incidental findings consisted of a malignant tumor) with breast, ovarian, renal, thyroid, colon, and prostate cancers most commonly discovered. It should be no surprise that this list consists of many of the most common cancers that people are familiar with.

Common Types of Incidental Findings

Many different types of incidental findings can be found in imaging studies including benign and malignant tumors and other pathological processes. Some of the more common ones include:

Atherosclerotic Plaque:

- Atherosclerotic plaque is a buildup of fatty deposits in the arteries and is a common finding on CTs of all body parts. They can calcify over time.

Calcifications:

- Calcifications are small calcium deposits that can be found in various organs on a CT scan. They can occur in stones (example: kidney stones, gallstones), be associated with atherosclerotic plaque (coronary artery disease), and be seen with various other processes.

Cysts:

- Cysts are fluid-filled sacs that can be found in any organ of the body. Cysts contain simple fluid and are nearly always of no clinical significance unless the cyst is so large that it pushes on adjacent structures. Cysts are incredibly common and frequently found in kidneys and livers.

Lymph Nodes:

- Lymph nodes are small, kidney bean-shaped structures that are part of the lymphatic system. They can be seen on ultrasound, mammograms, CT, or MRI exams.

Tumors:

- Tumors can be benign (non-cancerous) or malignant (cancerous). They can be found in any organ and are most often seen on ultrasound, CT, or MRI.

While not an exhaustive list, some of the most commonly encountered incidental findings are covered in the next sections.

Circulatory System (Blood Vessels)

Coronary Arteries:

Coronary artery calcifications are one of the most common and most important incidental findings that we make. Risks of coronary artery disease vary depending on the amount of coronary calcium, patient age, gender, and race. Higher amounts of coronary artery calcium are associated with higher levels of cardiac events and mortality related to coronary artery disease (CAD) such as heart attacks. When discovered, patients can undergo risk factor assessment, health and lifestyle changes, and be treated with various medications depending on patient risk factors and test results.

Aorta and Major Branch Arteries:

The aorta – the largest of the blood vessels supplying blood to the entire body – can have atherosclerotic plaque (calcified and/or non-calcified) and can form aneurysms (where it is dilated larger than normal). Ascending thoracic aortic aneurysms (where the aorta comes off of the heart in the chest) and abdominal aortic aneurysms are at increased risk of rupturing (bursting) over time, which is typically fatal. With risks including instant death, an aortic aneurysm is a “must make” diagnosis that can save lives. Large aortic aneurysms typically undergo imaging surveillance once detected and may require surgery for definitive treatment after they reach a certain size threshold.

All major branch arteries arising from the aorta can have significant narrowing or even be occluded, from the carotid arteries supplying the brain to the femoral arteries supplying the legs. Carotid artery disease, for example, can lead to stroke.

Lungs and Legs:

Pulmonary emboli (blood clots in the lungs) and deep venous thromboses (DVTs; blood clots in the legs) are uncommon incidental findings that can also be life-saving.

Neurological System (Head, Neck, Spine, and Nerves)

Meningiomas:

Meningiomas are benign tumors that arise from the covering of the brain, known as the dura mater. Meningiomas are frequently of no significance; however, they can grow so large that they start compressing the nearby brain and a small percentage are malignant and require surgical resection (removal).

Age-Related Changes:

Age-related senescent changes related to microvascular ischemic disease (white mater changes, brain volume loss/shrinkage, etc.) are very commonly identified on imaging of the brain. As we age, our brains gradually shrink and age right along with us. These are common and expected incidental findings in the elderly. Evidence of old strokes is also frequently identified on routine imaging.

Brain:

Brain aneurysms arising from the arteries of the brain are another potentially life-saving incidental finding that can be discovered in otherwise healthy people.

Other Head and Neck Findings:

Enlarged lymph nodes and salivary, parotid, and thyroid gland lesions can be seen on imaging of the neck and can be reactive or malignant.

Thickening of the aerodigestive tract is also occasionally seen and may require direct visualization by an ears, nose, and throat (ENT) surgeon to ensure they are not malignant.

Vertebral lesions may be identified on spine imaging and may require additional imaging examinations for characterization such as an MRI or nuclear medicine bone scan.

Mucosal disease, sinusitis, and dental disease are other common entities.

Cardiothoracic (Chest)

Lungs:

Pulmonary nodules are the most common incidental finding made in the chest, the vast majority of which are benign. Many are related to prior infection or granulomatosis disease (the body’s reaction due to prior bacterial or fungal infection), particularly in locations where histoplasmosis and coccidioidomycosis (common fungal pathogens) are prevalent.

Lymph Nodes:

Enlarged lymph nodes are most commonly reactive in the setting of infection. Enlarged lymph nodes can also be malignant (e.g., lymphoma, metastases from other cancers) or related to underlying inflammatory conditions such as sarcoidosis.

Thyroid Glands:

Thyroid nodules, which are often frequently discovered on neck CTs as well, can be benign or malignant and are found in patients of all ages including in young patients in good health. Nodule size and patient age are factors determining if further evaluation with thyroid ultrasound is necessary.

Breasts:

Breast masses are occasionally incidentally identified and require further workup with diagnostic mammography. Incidental breast lesions have a relatively high frequency of being malignant and their detection is incredibly important. Thankfully, screening mammography catches most breast cancers at relatively early stages.

Vascular Findings in the Chest:

For vascular findings, see “Circulatory System” above for a list of vascular findings in the chest.

Abdomen and Pelvis

Adrenal Glands:

Adrenal nodules are quite common (found in ~3-7% of adults) and most frequently represent benign adenomas. However, malignant cancers can spread to the adrenal glands and, rarely, primary adrenal malignant tumors may exist (pheochromocytoma, adrenocortical carcinoma). Benign features such as chunky calcifications, low density (lobules of fat or intracellular lipid – individual cells with a high-fat content), and >1 year of stability can confirm benignity.

Unfortunately, most adenomas are indeterminate on contrast-enhanced CT and further evaluation is necessary before the nodule can be safely ignored. Most nodules are non-hyperfunctioning adenomas (they simply exist for the sake of existing) though some nodules may “hyperfunction” and produce adrenal hormones. In these cases, a one-time endocrine workup may be helpful.

Kidneys:

Renal masses are fairly ubiquitous with the majority of patients having at least one renal cyst or two. Renal cysts are benign lesions that can be ignored. Probable cysts identified on non-contrast CT (contrast is necessary to confirm the mass is just a cyst) can be confirmed with ultrasound.

Renal lesions with a density greater than simple fluid on CT can either represent solid masses or hyperdense cysts, consisting of blood products or proteinaceous debris and require multi-phase contrast enhanced CT or MRI for definitive diagnosis.

Pancreas:

Pancreatic findings include calcifications from chronic pancreatitis, solid pancreatic lesions such as adenocarcinomas and neuroendocrine tumors, and a spectrum of cystic lesions most often consisting of side branch intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMNs). Pancreatic lesions typically require further evaluation with a pancreatic mass protocol MRI or CT and/or follow-up (typically for cystic lesions). MRI is preferred for cystic lesions.

Liver:

Liver lesions consist mostly of benign cysts and benign hemangiomas; however, hemangiomas frequently require multi-phase contrast-enhanced imaging for definitive diagnosis as hemangiomas demonstrate a fairly specific enhancement pattern (buzz phrase: discontinuous peripheral nodular enhancement with centripetal filling). The liver is a common organ for cancers to spread (metastasize), hence why confirming the benign nature of the lesion is important.

Large Bowel:

The bowel is frequently somewhat limited in evaluation on conventional imaging as it is typically filled with stool, but occasionally we find masses and polyps.

Ovaries:

Ovarian lesions are commonly found incidentally and also account for a higher proportion of incidental malignant tumors. Ovarian lesions are generally not well-assessed by CT aside from size and most incidental cysts are relatively small and can be ignored, especially in pre-menopausal patients. Larger lesions and any potentially solid lesion will require an ultrasound to better assess the lesion.

Uterus and Cervix:

Uterine fibroids are common, frequently irrelevant benign lesions found incidentally. Endometrial thickening in a post-menopausal patient and cervical masses (in any age) are infrequently found and require further workup imaging with ultrasound. Cervical lesions can also be assessed with direct visual inspection with a speculum exam and pap smear.

What is the Significance of Incidental Findings?

Some incidental findings can be life-saving or their discovery can be life-altering. It is important for radiologists to accurately report incidental findings, particularly those that may be clinically important, and try their best to determine the significance of each finding.

When the significance is uncertain, radiologists should include relevant follow-up recommendations based on consensus guideline recommendations. The goal is to guide ordering clinicians on how best to manage their patients depending on the patient’s health, risk factors, age, etc. based on the research available and ensure whether a finding is important or can be safely ignored.

Clinicians should be encouraged to call the radiologist with any questions they may have, particularly if they have additional clinical information that may impact the radiologist’s interpretation. Lack of information is probably the problem we most frequently face as radiologists. Information is power and teamwork makes the dream work!

Why Do So Many Incidental Findings Require More Tests?

Unfortunately, we don’t always have all of the information we need to characterize an incidental finding and are unable to rule out bad actors such as cancer. Believe me, radiologists also wish our scanners and PACS (picture archiving and communication system – our computer workstations) worked like crystal balls, but alas, they do not (otherwise I’d be scanning a piece of paper with “what are today’s winning lottery numbers?” all the time…).

Multiple factors can prevent us from being able to determine what a finding is. Some examples include: lack of intravenous contrast, patient motion, lack of multi-phase imaging required for the diagnosis of some tumors (such as liver and renal masses), low dose CT technique (screening exams such as lung cancer screening), lack of prior imaging (we love priors – a 3 cm adrenal nodule with > 1-year stability can be safely ignored), the finding is only partially visualized (part of a renal mass on a chest CT), and others.

When we make incidental findings on radiology examinations, our goal is to make a recommendation to guide the next steps based on current evidence-based consensus guidelines from the radiology literature and research articles. Unfortunately, these findings are often unrelated to the indication for the imaging exam they’re discovered on and therefore identified on examinations not tailored to assess many incidental lesions. For these indeterminate entities, we recommend examinations or tests that will help further characterize the indeterminate structure/process so we can find out what it is and if it is significant.

How Do Radiologists Decide What Tests To Order?

Our main source for information and consensus guidelines is the American College of Radiology (ACR) White Papers, which specifically address various incidental findings. These consensus guidelines are drafted by experts in the field and frequently based on the current literature (research) as well as expert opinion when there isn’t sufficient research to prove a benefit. Each White Paper has a narrow scope focused on a specific organ and contains a consensus guideline algorithm for radiologists to base their reporting on. Each algorithm contains several pathways dependent on different clinical conditions based on the available literature or expert opinion. The experts perform a cost versus benefit analysis when creating guidelines and take into account the costs of future testing.

Our goals when making incidental findings include: characterizing indeterminate findings (recommending additional examinations to figure out what an indeterminate finding is – to diagnose it), defining their clinical significance, if any, and providing information regarding follow-up recommendations for clinically relevant entities. For example, adrenal nodules are commonly discovered incidentally, present in ~3-7% of adults, and could be either benign (non-cancerous) or malignant (cancerous). We recommend a specific adrenal protocol CT to characterize the lesion and prove whether the nodule is benign and can be safely ignored or is malignant and requires a biopsy or surgical removal. This will vary depending on the nodule size and the clinical context – does the patient have a known history of malignant cancer?

How to Best Manage Incidental Findings?

For Patients:

If you have an incidental finding in your imaging study, the first thing you should do is talk to your ordering provider. Providers (doctors, nurse practitioners, physician assistants) may order additional exams and/or laboratory tests promptly so that any clinically important findings are managed quickly and appropriately. The next steps will be dependent on the test results and any relevant clinical information you can share with your provider.

While being told that you need additional tests can be nerve-racking, missing cancer or a potentially life-threatening condition is far worse. Cancers are best treated when detected early, minimizing the risks of cancer spreading and maximizing your overall health and well-being. Incidental findings can be scary, but it is important to remember that most of them are benign and pose no threat to your health. It’s better to be safe than sorry.

For Providers:

As radiologists, we will do our best to identify anything abnormal that is of possible clinical significance on every exam we interpret and supply evidence/research-based guidelines when available. We will provide guidance as best as we can, but ultimately we rely on you to assess each patient’s risks and underlying health conditions to lead to an accurate diagnosis. We don’t always have sufficient information and that is why we recommend clinical correlation – to help answer any questions we aren’t able to address. The value of teamwork? Saved lives!

Counseling patients is incredibly important to appropriately set expectations and alleviate or minimize any fear or anxiety they may have. Setting appropriate expectations is incredibly important and will not only help put the patient’s mind at ease but also likely increase compliance. The vast majority of incidental findings are benign and finding clinically significant entities in earlier stages before they become symptomatic is still a win.

Always remember that our goals are the same: to maximize patient health and safety by following trusted research-backed guidelines.

Summary

Incidental findings in radiology are common. They are often benign and pose no threat to a patient’s health. However, ~11% of incidental findings may be malignant and it is therefore important to follow them up to ensure these incidentally-detected cancers are diagnosed and treated rapidly.

For patients: talk with your provider, ask questions, and undergo recommended testing promptly. Solving the mystery of incidentally-detected entities can lead to as well as help quell any anxiety you may experience. Regardless of the outcome, you can feel reassured that the finding is either benign and can be safely ignored or was caught earlier than it otherwise would have, which can have a substantial effect on your health and well-being. We’re all in this together!

Found this helpful? Consider buying me a coffee to support more educational content like this! ☕✨